Dancing, singing, reflecting and learning: an encounter between Julián Díaz and a group of teachers in Chocó

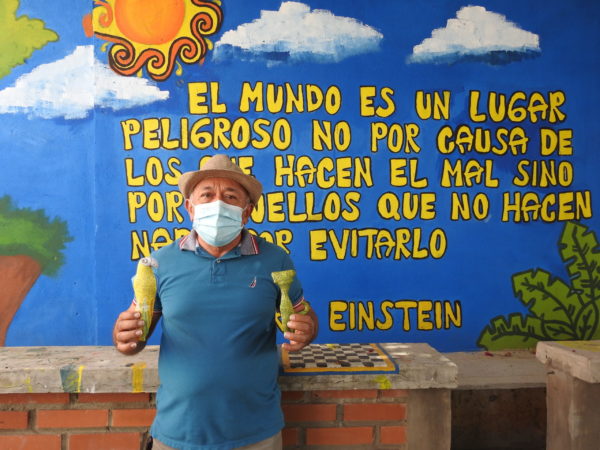

To say that Julián Díaz has got the magic is to fall short. The Colombian actor and co-director of Diokaju Generación Afro Art, is able to make anyone laugh, dance and shout. Julián brings smiles to those who are sad, makes those who do not want to laugh cackle and makes those who do not want to jump start jumpling all around. Then, the body is freed, emotions are released, reflection is triggered and learning is never forgotten.

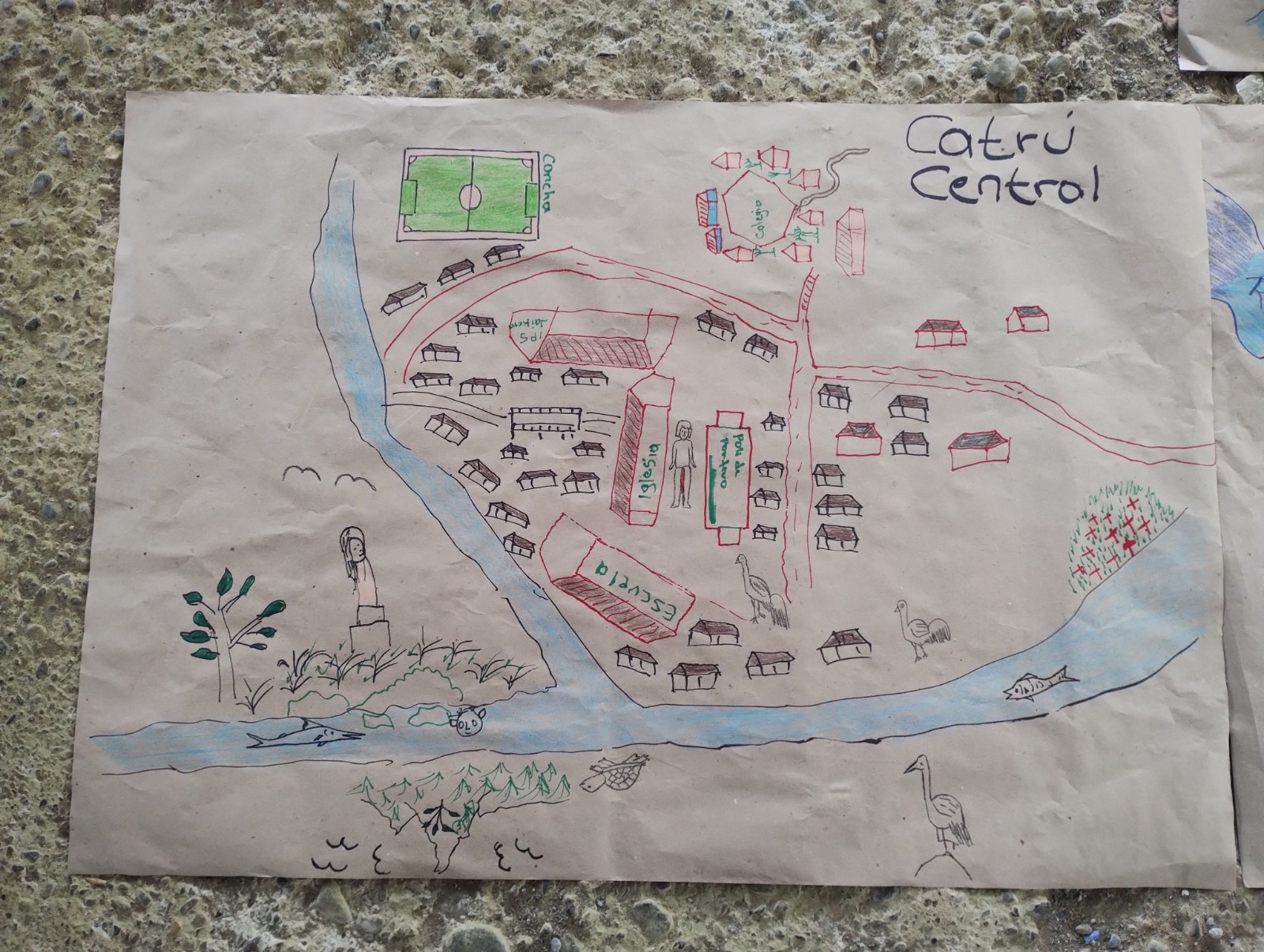

Julián’s indescribable magic reached several municipalities in Chocó. Together with Click+Clack and Unicef Colombia, as part of the ECHO project, the actor visited Pie de Pato, Platanares and Puerto Meluk (Baudó subregion), taking conversations, dances, songs and activities for teachers in the communities to explore different ways of learning and teaching.

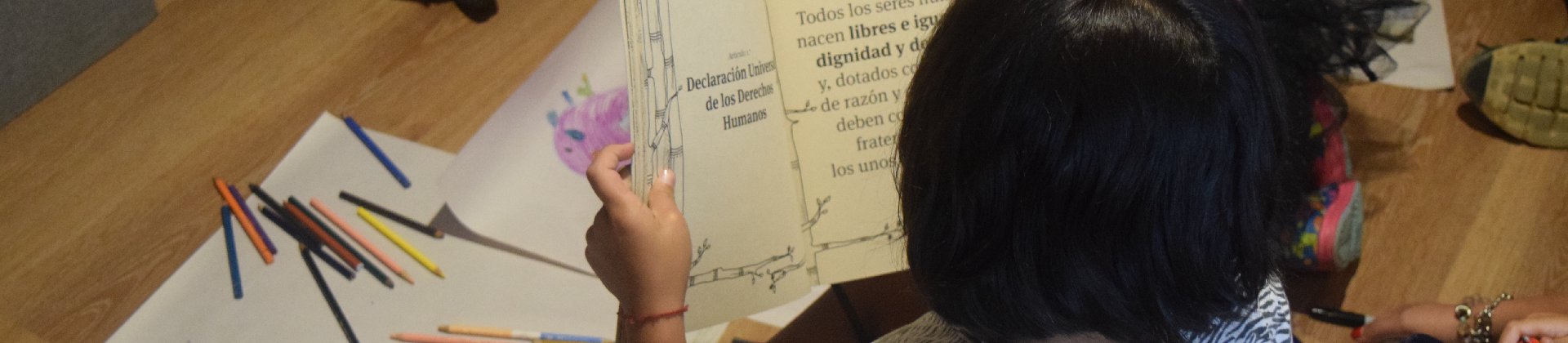

During this encounter with the communities, Julián managed to create spaces for relaxation and reflection with the teachers. Through postures, physical exercises, deep breathing, songs and dances, teachers memorized choreographies and danced around a candle that symbolized the guiding light of knowledge that we carry inside. The goal of this routine, beyond fun and stress release, was to make teachers aware of the importance of their work in society, the commitment that involves working with children and adolescents, and how learning processes can occur in any scenario.

Julian was able to trigger important reflections, for example, the need to create pleasant and empathetic environments to build trust, strengthen classroom participation, and trigger meaningful learning. In addition, the importance of focusing on activities aimed at collective well-being and the need to recognize the various strengths, skills and qualities that can be exploited in the academic field was highlighted. The relevance of putting emotions at the center of learning was another axis of the activities and dialogues triggered by the actor.

“I think that the activities carried out by Unicef and Click+Clack with teachers from three establishments in Alto Baudó, are a great opportunity for us to reflect on the way we experience our emotions and, therefore, to learn to guide them, transmit them or experience them with all those around us, especially with our students, to educate by example and get them to live a life in community enjoying and managing their emotions. This is another opportunity for us to improve what we do as teachers. Teachers work for many goals and we want to do it well. The opportunity that they gave us was beautiful. I felt that we all enjoyed it. It was very valuable and the most important thing is that it’s not stopping there; we know that we must continue working and not give up on children, or ourselves. I am very grateful and I hope that for my colleagues this will continue to be another way to keep enjoying what we do.” Glemi Samira Robledo, headmistress of the Hermano Anselmo Molano Educational Center in Alto Baudó.

Chocó is characterized by a high level of social and political unpredictability. The context of poverty and the lack of state presence, combined with the emergencies caused by floods and armed conflict, have affected the educational trajectory of children and young people in these communities. All this translates into enormous social and educational challenges. Therefore, it is essential not only to reach them with innovative and appropriate resources and materials, but to foster spaces where body, mind and emotions become protagonists of the responses to the needs that communities face.